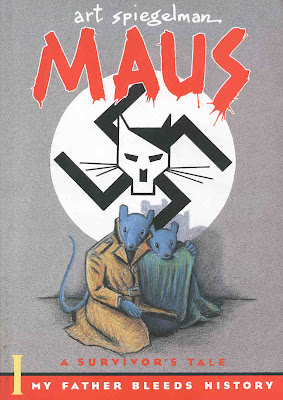

After letting it sit in my reading list for about 5 years, I finally took the time to read both volumes of Art Spiegelman's Maus, critically acclaimed and widely recognized as a highly influential work in bringing about an awareness of a graphic novel's capabilities as substantial literature. If you're even remotely considering giving comics a chance to be taken seriously, you need to read this book for its artistic and historic significance.

After letting it sit in my reading list for about 5 years, I finally took the time to read both volumes of Art Spiegelman's Maus, critically acclaimed and widely recognized as a highly influential work in bringing about an awareness of a graphic novel's capabilities as substantial literature. If you're even remotely considering giving comics a chance to be taken seriously, you need to read this book for its artistic and historic significance.The true-life story of Spiegelman's father surviving as a Jew in WWII Nazi prison camps (including Auschwitz) is not a new one (there are many holocaust survival tales out there), but is nonetheless important, insightful, and engaging! Yes, be prepared to experience the emotions of horror and sadness as the author recounts some of the hell wrought by Hitler and his goons, but also prepare for some thought-provoking questions that will give you something new to mentally chew on.

For me, some of these new questions/learnings were:

- With all of these tales about holocaust survivors, we tend to put them on a pedestal and laud their bravery and tenacity, among other amazing qualities. But what of those who DIDN'T survive? Are they less deserving of praise/recognition, any less brave/strong? It seems like there is a simple answer at first, but how does society generally, really respond to this question? Maus reminds us that, while willpower and strength played a part in the ability to survive the terrors of WWII prison/labor/death camps, perhaps the largest factor that determined who lived and who died was mere luck of the draw.

- Does holocaust survival really "end" with the end of the holocaust? What of post-holocaust life, recovery, and endurance? And how does the holocaust affect the next generation -- the survivors of the survivors? Maus certainly gives some interesting insights into this and makes this horrific part of world history more personal, while at the same time more impacting as we see the lingering effects of mass murder and torture still raging in the world over 50 years (at the time of the book's writing) after it was stopped.

- What is the purpose of writing about the holocaust? How does it affect the author, and what does our (as a nation) reaction to it influence its message (specifically in a negative connotation)?

- Basic cartoons with minimal lines generally make it easier for the reader to associate with the

characters therein. Don't believe me? Imagine if Garfield were told with photographic realism. Putting yourself in the shoes of Jon Arbuckle would be much more difficult, psychologically, because the detail doesn't allow for your mind to fill in the gaps and be quite as interactive. If Jim Davis used photographs instead of drawings, his readership would likely be very different. (I hesitate to say that the readership would drop, because I don't think a higher level of photorealism is bad -- it just expresses itself differently and would probably affect the thematic and narrative content of the comic).

characters therein. Don't believe me? Imagine if Garfield were told with photographic realism. Putting yourself in the shoes of Jon Arbuckle would be much more difficult, psychologically, because the detail doesn't allow for your mind to fill in the gaps and be quite as interactive. If Jim Davis used photographs instead of drawings, his readership would likely be very different. (I hesitate to say that the readership would drop, because I don't think a higher level of photorealism is bad -- it just expresses itself differently and would probably affect the thematic and narrative content of the comic). - Similarly, given Spiegelman's desire to use animals to represent real-world people, more simplistic line art makes such otherwise-fantastic scenes easier to take in. If he'd drawn the fur and bone structures more realistically, and thrown in various gradients of shading, the reader would constantly be aware of how ludicrous it is to have cats and mice walking upright, wearing clothes, and reenacting scenes from the Holocaust. It's just more effective this way for this particular story.

6 comments:

One of the things I found so intriguing about MAUS was the way that Spiegelman depicts the people as animals (mice, cats, pigs, etc.) to represent the way we stereotype people, and then how he breaks it down later by drawing some characters inconsistently as one species or another and how he breaks it down even more in volume two by drawing them not as animals, but as people wearing animal masks. He even draws the reader's attention to it by explicitly talking about his shrink having pet dogs and cats and asking the reader flat out whether it is consistent with MAUS' overarching metaphor.

You'll have to lend me this one over Christmas break! Well-written review.

That's really interesting, the point you made about how the art is more evocative because of its simplicity. I've never thought about it that way, even though I guess that's the idea behind minimalism to some or a large extent, isn't it? Very cool.

I haven't read this yet, but Spiegalman is gonna be the keynote speaker at AWP in February so I'll have to be sure to read MAUS before then!

Spiegelman is going to be on the reading list for one of my classes next semester. I'm guessing it's going to be MAUS.

Good review, lad.

JKC - thanks for that insight. I didn't feel like any characters were drawn inconsistently, but there are one or two parts where, for example, a pig isn't trusted simply because he's the only non-mouse in the camp. And unless I am recalling incorrectly, I believe Spiegelman only uses humans in animal masks at the beginning of volume 2 when he is recounting his experience of volume 1's critical success. I spent a few minutes thinking about the significance of this... I think you may be spot-on, though. The wearing of masks long after the Holocaust is over perhaps represents the lingering stereotypes we insist on creating for each other, seeing one another not as we are now, but rather based on events that transpired decades ago (it would be like meeting a German woman born in the 80s and not getting over the fact that her grandfather could have been a Nazi).

Erin - Consider it done. I also want Amanda to read it soon.

Amanda - Yes, minimalism is really interesting to study. There is a reason why children enjoy cartoons so much. It's funny because we, as a society, have labeled cartoons as a thing of immaturity, when in reality their simplified visual style often make for a more natural entrance into the narrative for the reader. Maybe it's not so much that children are being childish as much as it's that children are still making sense of the world around them and find cartoons/animation to be a natural outlet for catharsis and imagination.

Cabeza - Do it. DO it.

The part I'm remembering is where Vladek talks about there being one guy in the camp who claimed to be German, but who the Germans said was Jewish. As Vladek tells the story to Artie, we see it played out in the panels. In one panel he's drawn as a mouse, and in the next, he's drawn as a cat, but in the end, he is a mouse.

I think the point is that it didn't matter what the guy was physically, because the stereotypes were so strong that the basically became reality regardless of what reality really was.

It's also interesting how (I don't remember where in the book it is) when Vladek describes the Typhus epidemic in the camp, and talks about walking over bodies to get to the toilet at night, there's a long panel that's a close up of his foot stepping on the bodies. One body is a cat, one is a pig, and two are mice. But in the very bottom corner, right next to the text (which, I think, means that it is meant to be seen) there is a human foot.

Pretty interesting stuff. It's really one of the best pieces of holocaust literature out there.

Post a Comment